After months of rumours, Facebook finally unveiled its digital currency plans – and they did not disappoint. The social media giant’s plans are far-reaching and have already attracted some well-known partners to back it. Is Libra really the best of the libertarian cryptocurrency and traditional corporate worlds combined?

When the social media giant with close to 2.4 billion people using the platform each month, launches a new digital currency, there is reason to pay attention.

Facebook’s Libra, clearly has the potential to quickly achieve vast scale, setting it apart from any other cryptocurrency and virtual or gaming currency around.

Facebook is well aware that in order for Libra to be successful, it needs to open it up, which is why it is seeking the support of other corporate backers and has announced that Libra will launch as an independent entity in 2020. Facebook apologises that the current state of technology doesn’t allow a digital currency to be simultaneously scalable (process hundreds/thousands of transactions per second) and be fully decentralised – without consuming half of the world’s electricity. Indeed, technology hasn’t yet made all this possible, but the status quo makes it very convenient for Facebook to launch Libra in a comfortable centralised way, whilst grabbing the world’s attention with the launch of a cryptocurrency on blockchain.

From a technical perspective, the current centralised governance means using a blockchain architecture is unnecessary (to add to the confusion, Libra claims to be a blockchain without blocks). But if indeed, Libra is to make good on its promise to start moving towards decentralised governance in 2025, then it makes sense to start on a blockchain right away.

How will Libra work?

The plan is for the Libra network to operate independently from Switzerland, but users will need a Libra ‘wallet’ to interact with it, and that wallet will be domestically regulated. Facebook is building the Calibra wallet, and contrary to Libra itself, Calibra will be wholly owned by Facebook. This makes sense: the value for Facebook is not in the Libra currency itself; the transaction data are the real treasure trove.

This data will be generated by the wallet app and Facebook claims it won’t mingle transaction data with its other data without user consent. The Calibra app will probably make efforts to get this consent by offering superior functionality.

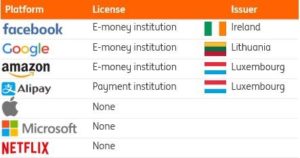

The biggest question right now is, how will regulators react? An e-money license (which Facebook already has in Europe) may not be enough for the Calibra app. Given that Libra is not denominated in domestic currency, but reflects a currency basket, it is probably more like security from a legal perspective. This takes us right back to the discussion that has been haunting cryptocurrency for years: is it a security or something else?

What about central bank and regulators?

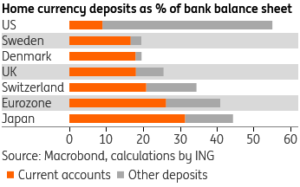

And there is more. The digital coin will be backed by a full reserve of low-risk safe assets, including government bonds. But the world’s supply of safe assets is limited. Central bank buying government bonds has increased scarcity in various parts of the world including the eurozone. If Libra becomes successful, it could develop into a significant buyer of government securities, which could potentially further push interest rates into negative territory. Germany, Switzerland, take note.

For years, central banks have been deliberating about cryptocurrency and central bank digital currency (CBDC). But with the introduction of Libra, Facebook has now accelerated this discussion significantly. It might be prudent and wait for regulators to formulate their view, or it may take the US-based ride-hailing service Uber’s approach and just launch, forcing regulators to respond (“shape a regulatory environment”, as they put it)

In any case, lawmakers and supervisors will have to decide quite quickly what Libra is, and how it should be regulated.

There are many more issues to think about. For example, the exchange rate risk users and businesses would face, how secondary market liquidity will hold in challenging times, and the impact all this would have on competition in various sectors.

While a lot remains unclear at this stage, Facebook has clearly started a new chapter on digital currencies. Over to policymakers for a response.

This article first appeared on ING THINK

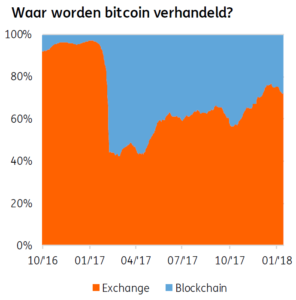

Maar de handelaren op de beurs hebben zelf geen cryptovaluta op de blockchain. Ze hebben slechts een claim op de beurs, toevallig uitgedrukt in cryptovaluta. Klinkt dat als een bankrekening? Daar lijkt het wel een beetje op. Met dit verschil dat er geen enkele regulering is voor deze beurzen. Het gaat dan ook wel eens mis.

Maar de handelaren op de beurs hebben zelf geen cryptovaluta op de blockchain. Ze hebben slechts een claim op de beurs, toevallig uitgedrukt in cryptovaluta. Klinkt dat als een bankrekening? Daar lijkt het wel een beetje op. Met dit verschil dat er geen enkele regulering is voor deze beurzen. Het gaat dan ook wel eens mis.