Een rustig en niet-technisch gesprek met presentator Hans van der Steeg over wat er nu allemaal aan de hand is, bij “Geld of je leven” op NPO Radio 1

Bron: Geld of je leven

Wie het weet, mag het zeggen

Een rustig en niet-technisch gesprek met presentator Hans van der Steeg over wat er nu allemaal aan de hand is, bij “Geld of je leven” op NPO Radio 1

Bron: Geld of je leven

Begin september sprak president Knot de verwachting uit dat De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) de komende jaren op haar buffers moet interen, en er wellicht zelfs volledig doorheen raakt. De centrale bank vraagt dan misschien de overheid om de tekorten aan te vullen.

DNB heeft sinds 2015, samen met de andere centrale banken in het “Eurosysteem”, grote hoeveelheden staatsobligaties opgekocht, om aldus de rente omlaag te duwen. Deze staatsobligaties staan nu op de balans van DNB, en brengen slechts hele lage rente-inkomsten binnen. Soms zelfs geen, gezien de negatieve marktrentes in de voorbije jaren. De afgelopen maanden heeft het Eurosysteem de monetaire beleidsrente in een paar stappen flink verhoogd om de inflatie te bestrijden, en het einde is nog niet in zicht. Dit komt er onder andere op neer dat DNB op de tegoeden die commerciële banken bij de centrale bank aanhouden, inmiddels weer rente betaalt. Tegelijkertijd krijgt DNB nog steeds nauwelijks rente binnen op de staatsobligaties die zij in portefeuille heeft. De rentebetalingen die DNB niet uit rente-inkomsten kan betalen, moeten dus “uit eigen zak” worden betaald. DNB teert in op haar buffers.

Maar zag het Eurosysteem deze verliezen niet aankomen? En had men zich hier niet beter op kunnen voorbereiden? Wel, toen in 2015 werd begonnen met het op grote schaal opkopen van staatsobligaties, hebben DNB en andere centrale banken direct gesignaleerd dat deze aankopen tot toekomstige verliezen zouden kunnen leiden, wanneer de rente zou gaan stijgen. DNB heeft daartoe sinds 2015 geld opzijgezet in de vorm van een voorzieningenbuffer. Alleen had men niet gedacht dat dit jaar de renteteugels, vanwege de sterk opgelopen inflatie, zo plotseling en zo hard zouden moeten worden aangetrokken. Dit betekent dat de rente-tegenvaller groter uitvalt dan eerder gedacht, en dat volgens de huidige verwachtingen de voorzieningen tekortschieten. Achteraf gezien had DNB een nog groter deel van de winst in de afgelopen jaren niet aan de overheid moeten uitkeren, maar opzij moeten zetten. Maar achteraf is het altijd gemakkelijk praten. Bovendien was zelfs dat mogelijk niet genoeg geweest.

Is het probleem niet eenvoudig opgelost als DNB stopt met rente betalen op de tegoeden van commerciële banken? Nee, want deze rentebetalingen vormen een essentieel onderdeel van het monetair beleid. Het Eurosysteem wil dat de rentes in de hele economie gaan stijgen. Door banken een hogere rente te vergoeden op hun tegoeden — en hen ook een hogere rente in rekening te brengen als zij geld lenen van de centrale bank — zullen de hogere rentes zich vertalen in hogere marktrentes. Bij hypotheekrentes is dit proces al enige tijd aan de gang, omdat deze sterker reageren op kapitaalmarktrentes dan op de monetaire beleidsrentes. Langzaamaan zullen ook rentes op spaarrekeningen gaan reageren op de monetaire beleidsrentes. Het opschorten van de rentebetalingen door DNB klinkt dus als een eenvoudige oplossing, maar zou in de praktijk de kern van het ingezette monetaire beleid ondergraven. Overigens bekijkt het Eurosysteem op dit moment wel hoe de rentekosten samenhangend met specifieke monetaire beleidsinstrumenten (de TLTRO’s, voor ingewijden), beperkt kunnen worden. Maar waarschijnlijk gaat dit de verwachte verliezen slechts mondjesmaat verkleinen.

Het interen op de buffers door DNB is dus een moeilijk te vermijden gevolg van het de afgelopen jaren gevoerde monetaire beleid. Bij normale bedrijven en banken wordt in het geval van negatieve buffers een faillissementsprocedure in gang gezet. Maar de centrale bank is natuurlijk geen normaal bedrijf. Negatief eigen vermogen staat de dagelijkse operaties niet in de weg. Een commerciële bank kan, bij (vermoede) financiële problemen, geconfronteerd worden met een “bank run”: mensen gaan massaal naar de geldautomaat, of vluchten naar andere banken. Maar bij de centrale bank bestaat dat gevaar niet. Wie met een eurobiljet naar het loket van DNB gaat, kan dat niet inwisselen voor goud of dollars.

Is er dan helemaal niets aan de hand? Dat ook weer niet. De centrale banken van het Eurosysteem vinden dat een situatie van negatief eigen vermogen niet te lang moet duren. Het kan, in hun ogen, namelijk wel de geloofwaardigheid van de centrale bank op financiële markten in de weg staan. En die geloofwaardigheid is nodig om effectief monetair beleid te voeren. Verlies van geloofwaardigheid zou bijvoorbeeld kunnen leiden tot koersdaling van de euro en verder oplopen van de inflatie.

Dat klinkt aannemelijk, maar niet iedereen gelooft dat een langere periode van negatief eigen vermogen een probleem is voor de geloofwaardigheid. De Tsjechische centrale bank bijvoorbeeld is het daar niet mee eens. En met reden: de Tsjechen hebben jarenlang met negatief eigen vermogen gewerkt, en daar naar eigen zeggen nooit last van gehad. Ook elders in de wereld zijn voorbeelden te vinden van centrale banken die langere tijd met negatief eigen vermogen gedraaid hebben.

Kortom: er wordt niet eenduidig gedacht over de effecten van negatief eigen vermogen bij centrale banken, en hoe lang zo’n situatie zou mogen duren. Toch valt niet uit te sluiten dat DNB, en andere centrale banken in de Eurozone, in de komende jaren een beroep doen op de overheid om het negatieve eigen vermogen aan te zuiveren. Gezien het gebrek aan consensus, ligt het voor de hand dat de overheid niet zomaar zal tekenen bij het kruisje. De onderhandelingen tussen DNB en overheid konden wel eens lang en interessant worden.

Origineel artikel verschenen als "ING Duik in de Economie" op 27 oktober 2022. Eerder, Engelstalig artikel hierover uit 2011 (!): Central bankruptcy: is it possible?

Central banks the world over have piled into central bank digital currency (CBDC) research and piloting. Problems identified by central banks are real and justify a response. Yet it is actually far from clear that CBDC is always the best solution to address the problems raised. Particularly in Europe, other policy responses may yield the same or better outcomes. This article looks at four prominent justifications for CBDC in the Eurozone: the need for access to public money in a digital world, the threat of large online platforms, excess dependency on non-EU payment solutions, and geopolitical considerations.

The European Central Bank Central (ECB) argues that “it is imperative to ensure that [people] continue to have access to central bank money” in an increasingly digital world. Public money is needed as a ‘monetary anchor’” (ECB 2022). But is it indeed the case that “private” money (such as bank accounts we all know and use today) can only function if people have access to central bank-issued money, such as banknotes and coins? The ECB-commissioned Kantar study (2022) into people’s payment habits struggled with the fact that many people don’t realise, understand or care about the difference between central bank and commercial bank-issued money. So perhaps people are perfectly happy to pay with digital “private” money, knowing that the central bank continues to be at the centre of the system, with a wide array of tools to guarantee the stability of money.

Large platforms are ideally positioned to integrate CBDC services into their payment system

The initial motivation for central banks to consider CBDC was to counter the threat of bigtech platforms issuing their own currency. Yet bigtechs issuing stablecoin not denominated in domestic currency, can effectively be addressed by regulation. The EU’s Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCAR) does exactly that, preventing such coins from becoming too large in payments. Meanwhile, domestically denominated stablecoins will require an e-money or banking license. Hence financial stability can be preserved by the full force of existing supervisory tools, and these coins are subject to domestic monetary policy as well. So why should CBDC be preferable over a well-regulated domestically denominated stablecoin?

But how then to prevent large online platforms from deploying digital currencies to increase user lock-in and further strengthen their dominant position? Well, legislative initiatives such as the Digital Markets Act seek to address this. And it is important to realise that platforms do not derive their lock-in power from issuing their own currency. Instead, they thrive by providing seamlessly integrated payments as part of an impeccable customer experience. As the BIS notes in a recent paper, a “core aspect of big tech business models is to run easy-to-use payment systems” (BIS 2022). In other words, it’s not about the underlying currency, it’s about the payment infrastructure on top of it. This means that a CBDC could in fact play into large platforms’ hands! Most of them are already licensed to act as Payment Service Provider. They are ideally positioned to integrate CBDC services into their payment systems, roll out solutions across Europe and thus further optimise their customer experience.

The digital euro is also positioned as a tool to avoid or reduce dependency on a small number of non-EU-based solutions. Yet here too the question arises whether the goal justifies the means. How is adding another form of digital currency going to help reducing existing dependencies? A CBDC will still need an infrastructure to actually use it for payments. A better targeted response to the concern of excess dependency would be to develop an alternative EU-based payment scheme for digital and online payments. Such a scheme could then process commercial bank money, stablecoin and even crypto payments – no CBDC needed.

Finally, an opportunity identified by policymakers is the possible use of CBDC as a tool to strengthen the euro’s position on global trading and financial markets. Yet a CBDC focused on a domestic retail audience, such as the digital euro, is unlikely to make an impact on such global markets. To strengthen the international role of the euro, a focus on large-value, cross-border and cross-currency payments would be needed.

Indeed the ECB and other central banks are looking into what is called “wholesale CBDC”, while private parties are also investigating digital currency platforms backed by central bank reserves. Yet wholesale digital currencies have very different characteristics and requirements than the retail variety. They are therefore generally treated as separate projects.

In short, while central banks and policymakers have put a number of very valid concerns on the agenda, it is highly doubtful whether a retail-focused CBDC is a sufficient or even necessary answer.

Article first appeared in Eurofi "Views" Magazine, August 2022.

The Ethereum blockchain is on the verge of a major and risky upgrade. This upgrade, if successful, would greatly reduce electricity use. This, in turn, would increase Ethereum’s acceptability to policymakers and financial institutions

After a long period of anticipation, and if final tests go well, the world’s second blockchain Ethereum will probably transition from “proof of work” (PoW) to “proof of stake” (PoS) later this month. This means that transactions on the Ethereum blockchain will no longer be recorded by miners that spend a lot of computing power to prove they worked hard to verify transactions. After “the merge”, transactions will be processed by validators, that have staked Ether (in other words, put collateral in escrow) that can be forfeited if it turns out they were acting in bad faith.

The discussion about the pros and cons of PoS vs PoW is almost as old as Bitcoin, and we can’t represent all arguments here. What we’re interested in, is that this transition to PoS may over time increase the acceptability of Ethereum, and all of the apps built on top of it, for policymakers and regulators. This in turn may provide a boost to traditional financial institutions’ willingness to develop Ethereum-based services.

Ethereum is not the first blockchain to adopt PoS. But it is generally considered the most important blockchain after Bitcoin, and Ethereum is a key building block of the decentralised finance universe. Moreover, Ethereum won’t go down for scheduled maintenance over the weekend to upgrade the network. Instead, as ethereum.org describes it, the new PoS-engine will be hot-swapped in mid-flight. A flight which hosts a variety of apps, tokens and platforms. What could go wrong?

Indeed, while the Ethereum community has spent a lot of time testing PoS (the PoS testing ground called “beacon chain” has been running since December 2020), implementing such a fundamental upgrade while the network keeps running, is ambitious. As anyone who has ever tried to quickly upgrade the operating system on their computer will know, there are almost always unexpected hiccups that end up taking much more time than anticipated. We expect leading Ethereum developers to be pulling all-nighters glued to their screens during the upgrade.

Another question during the upgrade is how Ethereum miners will respond. They have invested in dedicated hardware, typically GPUs, that can no longer be used for mining Ethereum after the upgrade to PoS. Some miners may decide to continue the PoW-based blockchain, creating a “fork”. Such a duplication of the blockchain with all its tokens creates a variety of problems e.g. for exchanges and traders. Luckily, the crypto community has gained experience managing such forks over the years.

Describing all these challenges, you may start to wonder why Ethereum embarked on this project at all. Apart from improved scalability, the main reason is a drastic reduction in electricity consumption. Ethereum.org claims a 99.95% reduction in electricity consumption following the switch to PoS.

An important non-technical consequence of this great reduction in electricity need is that it may render Ethereum more palatable to policymakers and regulators. When the European Parliament discussed the EU’s incoming Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation earlier this year, sustainability was an important topic. Policymakers are uncomfortable with the PoW consensus mechanism’s high electricity use. To be sure, the pros and cons of PoW vs PoS are food for a fundamental and often heated debate, which has many more nuances than the –admittedly impressive– kWh figures suggest. We cannot do justice to this debate in this short piece. It is clear though that the switch to PoS removes power consumption as a problem for regulators. This, in turn, removes one stumbling block for traditional financial institutions and other companies to offer Ethereum-based services, although other obstacles may remain.

So what’s not to like about PoS? Apart from migration risks, PoS has its own challenges. For example, its code is much more complex than PoW. This may create new vulnerabilities. Hackers will certainly be exploring the new infrastructure for flaws. Another issue is that PoS creates a new form of inequality. With PoW, there once was a sense that everybody can join in and start mining. With PoS, in contrast, the “wealthy” can stake a lot of Ethereum and reap most of the validation rewards, further increasing their wealth. Yet the reality is more nuanced. PoS staking pools do provide opportunities for those with less Ether to spare. And with PoW on the other hand, the days that an old laptop was sufficient for mining, are long gone.

Some people worry about increased possibilities for censorship by PoS validators. Yet in principle, PoW miners could apply censorship as well. It is also not evident that PoS will lead to a more concentrated validator landscape than PoW, where miners have been cooperating in mining pools for a long time. In the end, it’s less the technology that makes the difference, but rather the attitude –and regulation– of those using it. More generally, there is a tradeoff between censorship resistance and the application of anti-money laundering and sanctions policies which are required to render cryptocurrency acceptable to regulators. In the end, compromises need to be struck here.

Ethereum’s upcoming migration from PoW to PoS may be the biggest planned event in cryptoland this year. The migration itself and its aftermath carry risks, and will be closely watched within the crypto community. A successful migration would be a compliment to the Ethereum community’s ability to manage big events. It would also remove an important obstacle to acceptability of Ethereum to regulators and hence development of Ethereum-based services by traditional financial institutions.

First appeared on ING THINK

The problems surfacing in crypto markets over the past weeks are well-known in traditional finance, as are the tools to address them. If this does not illustrate why crypto regulation is welcome, what will?

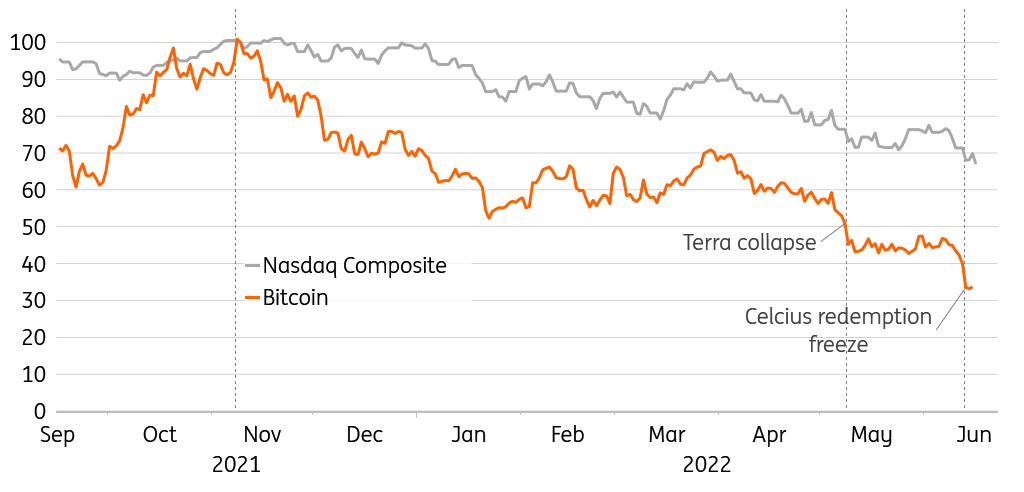

While all financial markets have been volatile of late, crypto assets in particular are having a very bad time. Leading cryptocurrency bitcoin is currently down 30% compared to a week ago. While crypto assets were, until not too long ago, seen by many as uncorrelated with traditional stocks, the crypto downturn since November has progressed in remarkable sync with traditional assets, tech stocks in particular. The common factors that drive down traditional markets – inflation and rate hike expectations – are weighing on crypto as well.

Moreover, where crypto appeared to enjoy an accelerator when markets were bullish, that same accelerator is now at play in the bear market. While the NASDAQ composite stock index has lost about a third since November last year, bitcoin has lost double that (see chart). This multiplier can probably at least partly be traced back to the build-up of leverage when times were good, and the unwinding of that same leverage over the past weeks and months. Indeed a number of prominent crypto investment names currently in trouble appear to suffer from margin calls on leveraged bets gone wrong.

Instrumental in the recent crypto market turmoil has been the crash of “algorithmic” stablecoin Terra, in early May. This type of stablecoin is not backed up by assets to guarantee its value, but deploys an algorithm trading in the stablecoin versus a companion currency. The idea was that the algorithm could always mint new companion currency to buy stablecoin, keeping up the value of the latter.

What worked for Baron von Munchhausen, does not work for algorithmic stablecoins

Yet the crucial assumption for this to work is that the companion currency is perceived to have at least some value. That assumption was proved wrong by the Terra stablecoin. As a result, its algorithm took the concept of “quantitative easing” to wholly new levels when it increased the supply of companion currency Luna more than 20,000 times (from about 350 million to over nine trillion at the peak), trying to prop up Terra. Alas, what worked for Baron von Munchhausen (getting out of the swamp by pulling up his own hair), does not work for algorithmic stablecoins in an environment of evaporating confidence.

The episode was perceived by regulators as a confirmation of the need to regulate stablecoin very much like a bank. That makes a lot of sense. Like a bank deposit, stablecoins are expected to always trade at par with the currency in which they are denominated. Stability, security and liquidity are key concepts. And like a bank, a stablecoin may face runs if confidence is tested. Banks have various mitigations and remedies in place, encouraged and imposed by regulation.

We expect algorithmic stablecoins to retreat to the margins of the crypto universe

Purely algorithmic stablecoins are unlikely to pass the regulatory bar, and we expect them to retreat to the margins of the crypto universe. Instead, stablecoins will likely have to be fully backed by high-quality liquid assets. In other words, stablecoins will be full reserve banks (as opposed to traditional banks that operate on fractional reserves). The full reserve operation means stablecoin issuers hardly face any credit risk, removing the need for a deposit guarantee scheme, and greatly simplifying the capital buffer framework, compared to traditional banks.

Regulators are rightly worried though that if stablecoins grow further their issuers may become systemically relevant. In case of a run and the need for asset fire sales to honour redemptions, even high-quality liquid assets may temporarily trade against a discount, imposing losses on the issuer and disrupting safe asset markets for the entire financial system. The crypto universe currently houses a few dominant stablecoins. The consensus is that these may not yet pose systemic risks as described but may well start to – if their volume issued continues to grow as it has done over the past years.

The crypto company that had to halt redemptions earlier this week – and in so doing started a new wave of panic – is different: it is neither a stablecoin nor a regulated bank, but for its main product offering it did use bank-like language such as “savings” and “deposit”. It also distinguished itself by offering double-digit yields that are impossible to find in traditional banking. The company has had various run-ins with US supervisors, that opined it was offering a securities product without proper registration.

Faced with a run, any institution that is in principle solvent, can turn illiquid

The crypto company did vaguely resemble traditional banks in the sense that its assets tended to be riskier than its liabilities tended to be perceived. Also, some of its assets appear to be locked up for a longer period, whereas its liabilities were immediately redeemable. Finally, the liquidity of some of its assets proved to deteriorate fast in current markets. These transformations of risk, maturity and liquidity are core functions of a traditional bank. They also render a bank susceptible to runs. Faced with a run, any institution that is in principle solvent (its assets are worth at least as much as its liabilities), can turn illiquid (it cannot liquidate its assets immediately at the right price to honour redemptions). For this reason, bank regulation may be the most elaborate type of regulation out there, including liquidity buffers to handle redemptions, capital buffers to absorb losses, detailed risk management, and transparency requirements. If, despite all this, a bank runs into trouble, the central bank can act as lender of last resort (against proper collateral), and if the bank does fail, deposit guarantee schemes (typically financed by the sector itself) ensure depositors don’t end up with a loss.

Mutual funds have the important difference that they don’t issue liabilities at par – meaning that contrary to banks, they pass on credit risks to their investors. Insofar as their assets are tied up for a longer time, they may impose lock-up periods on investors wanting to redeem.

To summarise, the problems currently faced by some crypto companies are well known in traditional finance, as are the tools to mitigate them. If regulation had been in place, risk-taking and leverage might have been more contained, or at least have been more transparent. Does regulation guarantee things never go off the rails? Unfortunately, no. But it would have established basic investor protection, and would have allowed them to realise that there is no such thing as a free lunch: high return typically comes with high risk. Our main takeaway from this week is therefore twofold:

First appeared on ING THINK

As crypto markets are brought under the regulatory umbrella, banks may find it easier to enter the field. Yet a number of issues still need to be resolved

The introduction of an EU regulatory framework for crypto assets edged one step closer in March as the European Parliament adopted the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCAR). We discussed the layout of MiCAR extensively here, but in this article, we focus on the implications for banks.

As crypto markets have grown and developed in recent years, so has bankers’ interest in them. Some banks are openly pondering the idea of offering crypto-related services, and some have stuck a toe in the water. The arrival of MiCAR would certainly make it easier for banks to offer crypto-related services, should they wish. MiCAR will make sure that separating the good and regulated from the potentially bad and ugly becomes a lot easier for customers, but that also applies to banks. They can transact and partner with fully regulated crypto counterparties. But it’s by no means plain sailing from here onwards. Here are a few considerations for banks:

While upcoming EU crypto regulation is a very welcome step forward and a key prerequisite for regulated financial institutions, it does not address all questions. For example, MiCAR has very little to say about DeFi lending. Another important question is to what extent stablecoins and central bank digital currencies will be allowed to co-exist. How crypto assets will be integrated into the EU’s sustainability framework will also shape traditional financial institutions’ presence in crypto services.

The upcoming EU crypto regulation is very welcome as it brings much-needed clarification of responsibilities. Yet as the crypto-universe develops very fast, a number of questions remain unanswered

Once upon a time, cryptoland was a sort of digital Wild West where it was entirely up to each individual to separate the good from the bad and the ugly. But those days are numbered. The EU already introduced anti-money laundering regulations a few years ago. More recently, financial sanctions have put the spotlight on the crypto universe, with some policymakers calling for accelerated regulation for the sector, though crypto companies are already obliged to implement sanctions just like any other business.

The US government recently decided to centralise and streamline the development of crypto regulation. But Europe is further ahead

It is true though that crypto regulation remains lacking in important other areas. The US government recently decided to centralise and streamline the development of crypto regulation. But Europe is further ahead. The European Commission launched its proposal for a Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCAR) back in September 2020. The European Parliament’s Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee adopted MiCAR with amendments on 14 March, and the regulation will now move to discussions among the European Commission, Parliament and Ministers of Finance (the so-called “trilogue”). Once they converge, MiCAR can be established. Of course at that point supervisors will need time to prepare the new regulatory regime and draft technical standards, explaining how they will interpret and apply concepts in MiCARs. Based on the European Council’s MiCAR draft, provisions on stablecoins would start to apply in early 2024, while other provisions would apply in early 2025.

That sounds like a long time, especially in the fast-evolving crypto universe. In the meantime, we could, for instance, witness another boom-bust cycle or the rise to fame of a completely new category of crypto asset. But two years is not that long either from a business planning perspective. This means now is the right time to get acquainted with MiCAR.

So what kind of rules does MiCAR establish exactly? Since the fifth EU anti-money laundering directive (AMLD5) came into force in early 2020, crypto services providers are subject to its provisions. For anti-money laundering purposes, and separately of MiCAR, the European Commission has made proposals to subject crypto-asset transfers to the same requirements as wire transfers. An important issue in this proposal, that we won’t discuss further here, is how to ensure sufficient information is collected on self-hosted wallets (crypto wallets that people manage themselves, instead of relying on a third party) while keeping requirements proportionate.

From the regulatory edifice perspective, anti-money laundering was only the first step. Regulation in other areas (see box) is practically non-existent in the crypto universe. This is set to change with MiCAR, which introduces crypto to the other three pillars.

The financial regulatory edifice can be broken down into four main pillars:

These four pillars constitute regulation specific to the financial sector. The sector is also subject to broader regulation and supervision, to guarantee fair competition and proper handling of data and privacy. As societal demands and technological possibilities evolve, regulation tends to become more stringent over time as well.

Given the breadth of policy goals, it should not come as a surprise that policy goals are sometimes conflicting and require a trade-off. Well-known trade-offs are between competition and financial stability (a monopoly might be financially stable, but undesirable from a competition perspective), and between privacy and AML/CFT. Such trade-offs are becoming apparent in MiCAR as well. Finally, it should be noted that promoting innovation is also a goal of MiCAR, by increasing customer confidence, reducing legal uncertainty and promoting a single EU market for crypto assets and services.

An important step forward is that MiCAR will introduce “passporting”, meaning that a coin notified or a crypto service authorised in one country can operate across the EU without having to register separately in each country. Furthermore, MiCAR aims to be complementary, meaning that where possible, crypto assets and service providers are to be covered by existing regulations. This means that when attempts would be made to “tokenise” securities trading, for example, the desired regulatory outcome would be that the tokens are considered securities from a regulatory perspective, with all the investor rights and issuer obligations (such as availability of a prospectus) that come with it.

If it looks, talks and waddles like a duck, we shall regulate it like a duck

Policymakers also tried to make MiCAR future-proof by making the regulation “technology-neutral”. This means applying the principle “same business, same risks, same rules”, which can be roughly translated as “if it looks, talks and waddles like a duck, we shall regulate it like a duck. No matter whether it’s a green or yellow duck, whether it dresses itself up as a pigeon or thinks of itself as a goose”.

This principle sounds clear and sensible but is a lot harder to implement in practice. In fact, it is almost inevitable that regulation is always trailing behind developments in the field. This applies in particular to a fast-evolving area like crypto. Still, it is likely that a substantial part of cryptocurrencies and stablecoins that we know today will move in scope of MiCAR, although it is much less clear to what extent decentralised finance will be in scope (see below). Utility tokens, granting access to a good or service provided by the issuer, are exempted from MiCAR under certain conditions. The same goes for non-fungible tokens (NFTs). The treatment of decentralised organisations also remains problematic. That being said, MiCAR distinguishes a few broad categories that will be subject to regulation. These are:

The main requirement for issuers of new cryptocurrencies is the need to publish a white paper containing “mandatory disclosures”. Regulators have clearly thought about the prospectus that must accompany each securities issuance but thought it better to adopt the terminology of the field. Notifying national financial markets supervisors about a white paper is enough, although supervisors can come back and demand a revision if the information contained in the white paper does not meet minimum standards.

Notifying national financial markets supervisors about a white paper is enough

Policymakers are struggling with what to do with crypto assets that are not issued by a legal entity – such as bitcoin. The draft versions of MiCAR by Commission, Council and Parliament differ on this point, and we’ll have to await what the final requirements will be. In any case, existing crypto assets are exempted from some requirements. In other words, bitcoin won’t be in violation of MiCAR by not having a fully compliant white paper.

The European Parliament has considered several provisions on sustainability, including a requirement for proof-of-work crypto assets to include an independent energy consumption assessment in their white paper (see paragraph below).

Stablecoins are subject to a heavier regime. From a customer protection perspective, the claim of “stable value” warrants demands about asset investment and redemption. From a financial stability perspective, stablecoins potentially claim a bigger role as means of payment. Mandatory investment by stablecoin issuers in low-risk liquid assets may also impact financial markets, by reducing the supply available. MiCAR distinguishes two types of stablecoins (while, by the way, avoiding the term as such):

The European Central Bank (ECB) and national central banks have the authority to limit the scope of ARTs or even ban them altogether if the ART threatens the “smooth operation of payment systems, monetary policy transmission, or monetary sovereignty”.

Algorithmic stablecoins tracking currencies or other assets will be considered ARTs. When an algorithm only endogenously manages coin supply in response to demand and does not aim to maintain stable value vis-à-vis an external asset, the coin may not qualify as ART.

For both ARTs and EMTs, the assets the issuer invests in should be high quality, low risk and liquid. This may include central bank reserves, but also Treasury bonds, among others. Unlike bank deposits, ARTs and EMTs cannot be backed by mortgages and corporate lending. Interest remuneration is not allowed, to avoid use as means of saving. Following the E-Money Directive, issuers should have a buffer (“own fund requirement”) of 2% of their reserve assets, with a minimum of €350.000. Above certain thresholds (specified in size and usage in transactions), ARTs and EMTs can be labelled “significant”. In that case, stricter requirements apply for capital buffers, interoperability and liquidity management policies.

Crypto asset service providers (CASPs) include, among others, custodians, exchanges and brokers. CASPs always need to be an authorised, EU-based legal entity. Their obligations include suitability and fitness assessments of their clients, and to always act “honestly, fairly and professionally in the best interest of their clients.” Like traditional exchanges, crypto-asset trading platforms are subject to various requirements to ensure market integrity, including trade transparency requirements. CASPs will also have a degree of liability for client losses as a result of hacks and outages.

Current regulatory frameworks are based on legal entities. In other words, rules apply to companies with an office address in the EU. Those companies can be authorised, held accountable, fined or if needed banned, while their offices can be visited and checked by supervisory staff. It often doesn’t work like that though in the decentralised crypto universe. True, a lot of crypto assets and organisations that claim to be decentralised really aren’t. Arguably, of the thousands of crypto assets and services providers out there, a large majority is a centralised venture in the end. They will be in scope of MiCAR.

But things get more complicated if, for example, a group of coders is collaborating voluntarily and on an unpaid basis on Github, releasing open-source wallets or client trading software. Where is the legal entity to license? Perhaps these coders have put a governance structure in place, voting on code changes and with admins signing off on them. Are those admins the “issuer” or CASP from a MiCAR perspective? Or the voting coders?

Another difficult example is the category of automated protocols creating decentralised exchanges. Sometimes there is a company that initially built the protocol but has released it in the public domain, and is not hosting or otherwise facilitating the protocol. Can the company be regarded as the CASP?

Then there is the universe of “decentralised finance” (DeFi), which largely emerged after the European Commission delivered its first draft of MiCAR. Indeed, financial services like lending and borrowing are not in scope of MiCAR. It should be noted that the EU framework includes other directives covering lending to households, and also a recent regulation covering crowdfunding. It remains to be seen to what extent decentralised finance fits within these rules.

MiCAR is clearly struggling with all of these issues. As yet, it is unclear how MiCAR will deal with decentralised coin issuance, decentralised autonomous organisations (DAOs) or DeFi. As a follow-up, the European Parliament is asking the Commission to present a report about the latest in crypto-land sometime after MiCAR has entered into force, including decentralised aspects. In addition, the Parliament is aiming to insert some exemptions for DAOs.

Government authority stops at the border, but the digital space is global. Other than issuing warnings, regulators can do little to stop EU citizens from shopping at their own initiative with CASPs headquartered outside the EU.

But allowing customers to casually walk in is quite different from actively soliciting EU customers or promoting and advertising services in the EU. This is only allowed for EU-based CASPs. Moreover, if a foreign crypto-asset issuer wants its coin to be offered or traded in the EU, it should notify a white paper just like EU-based issuers. If it’s an ART or EMT, EU legal presence is required as well. Alternatively, if an EU exchange wants to list a non-EU based coin the exchange can take on the obligation as if it were the EU-based issuer of the coin. In that case, under MiCAR the exchange will be treated, and held liable, as the EU issuer for that coin.

Bitcoin, in particular its “proof-of-work” mechanism to achieve consensus on the transactions to add to the blockchain (the process of mining), is energy-intensive. This in itself is hardly disputed. Yet there are many more nuances to this debate. Issues include the carbon footprint of the specific energy source used and the extent to which crypto electricity demand substitutes for other demand or whether otherwise wasted energy is used. A more normative question is whether bitcoin offering an independent, globally available, decentralised and censorship-resistant transaction ledger justifies its electricity use. And how does crypto energy use compare to data centre energy use for storage and distribution of social media, games and funny cat videos?

Several crypto protocols have limited energy use, but this typically comes at the cost of less decentralisation

While several crypto protocols have limited energy use by, for example, relying on alternative “proof-of-stake” consensus mechanisms, these alternatives typically come at the cost of more limited decentralisation. The community governing bitcoin’s codebase is likely to take a conservative stance, not pioneering alternative consensus mechanisms that compromise on decentralisation.

The discussion about crypto electricity consumption has probably been the most controversial aspect of crypto regulation in the European Parliament. An amendment to bar crypto assets based on environmentally unsustainable consensus mechanisms from trading in the EU did not make it, though it may reappear in further negotiations. Such a prohibition to trade energy-intensive cryptocurrencies would effectively boil down to a bitcoin ban, which would be a blow to the EU’s crypto sector. Bitcoin’s dominant position in the crypto-sphere may be eroding as other cryptocurrencies (stablecoins in particular) gain ground in “decentralised finance”, but bitcoin still functions as the reserve currency of crypto. A ban would push bitcoin-related activity to service providers outside of the EU, and hence out of sight of EU supervisors. A bitcoin ban would thus undermine the foundations of MiCAR.

A less controversial approach would be for cryptocurrency consensus mechanisms to be included in the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities. One way would be for some consensus mechanisms to be earmarked as positively contributing to climate change mitigation. This would provide some positive incentives for energy-conscious cryptocurrencies. It would not significantly hinder, let alone ban, energy-hungry ones.

A more intrusive approach would be for consensus mechanisms like bitcoins proof-of-work to be earmarked as unsustainable. Importantly, this first requires the inclusion of unsustainable activities in the EU taxonomy, which currently only identifies sustainable ones. If indeed proof-of-work would be qualified as “significantly harmful” to environmental sustainability, this would make it less attractive for financial institutions and other businesses to hold bitcoin. It would lower the sustainability score of their assets which they will need to disclose. While these disclosure requirements may not immediately deter dedicated crypto companies, they would provide a disincentive for more traditional financial institutions, in terms of reputation, but also in terms of funding costs.

Some institutions in the “traditional” financial sector, including banks, have been openly pondering the idea of offering crypto-related services. But that is easier said than done. Banks have to figure out difficult issues, such as the business model of any crypto-related services and duty of care towards their clients. Moreover, the fact that the crypto space is unregulated except for AML makes it very difficult for banks, being arguably the most regulated institution around, to participate. MiCAR is an important step forward in reducing regulatory uncertainty. Another important aspect – the prudential treatment of any crypto-exposure on banks’ balance sheets – won’t be covered in MiCAR, but in the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). The Basel Committee issued a first consultation last year on prudential treatment.

MiCAR stipulates that stablecoin issuance requires an e-money license (for small stablecoins) or a banking license. Arguably this makes banks well-placed to consider issuing stablecoins from a regulatory perspective. Yet the business model of issuing a stablecoin is not evident. Stablecoin issuers will make an interest margin on their assets, given that interest remuneration on stablecoin holdings will be forbidden. Yet while a “normal” bank can lend to households and businesses, stablecoin issuers are confined to investing in high quality and liquid assets. This will limit their interest margin. There may be a better business in offering stablecoin-related services to clients, than in issuing them.

The strong central bank powers to effectively ban stablecoins, is a Sword of Damocles hanging over any initiative

Moreover, the strong power MiCAR bestows on central banks to effectively ban stablecoin if they become too influential is a Sword of Damocles hanging over any stablecoin initiative. The strong backlash against Facebook’s Libra (later Diem) makes clear that policymakers and supervisors will not necessarily be very welcoming towards stablecoins. Meanwhile, the ECB is working on the “digital euro”, which can at least in part be seen as an alternative or even competitor to private stablecoins. So the ECB, as likely future digital euro issuer and stablecoin assessor, has a potential conflict of interest that may not turn out well for prospective stablecoin issuers.

The EU’s Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation is meant to bring clarity for both customers and the crypto industry. Customers should be able to pay, invest or trade with confidence, while innovation should be promoted. So, does MiCAR meet these ambitious goals? The answer to that is nuanced:

| Glass half empty | Glass half full |

|---|---|

| Regulation always trails technological advances and market developments, in particular in the fast-moving crypto world. MiCAR has regulatory white areas, such as new services developed in decentralised finance or truly decentralised organisations. It does not apply to most non-fungible tokens (NFTs). It will take another two to three years for it to apply in full. Meanwhile, the crypto universe will develop further. | MiCAR provides a basis to work from and provides decent clarity on the direction authorities want crypto to evolve. A lot will depend on how supervisors will use the discretion they will inevitably have. |

| While MiCAR establishes a single EU framework, there are other applicable laws that largely work at a national level, in particular around money laundering and terrorism financing. | MiCAR will allow “passporting”, meaning that authorisation in one member state allows coins and crypto services to be provided throughout the EU. |

| Authorities take a very strict approach towards stablecoins. Heavy licensing requirements and sweeping authority for central banks to intervene make the business case for a stablecoin uncertain. It is unclear if stablecoins will need to participate in deposit guarantee schemes, which would further weaken their business model | Applying bank regulation to larger stablecoins will provide customers with the necessary confidence in the coins being able to make good on their stability promise. A competitive and innovative field of payment services may develop on top of traditional bank deposits, stablecoins, and central bank digital currencies. |

It is clear that MiCAR brings sweeping changes to the crypto sector. The arrival of a dedicated regulatory framework can be considered an important step in the coming of age of Europe’s crypto markets.

First appeared on ING THINK

Although two years to investigate sounds like a pretty long time, there is a lot to discuss, and many things to get right before launching a digital euro. But first up, decide on the main goal

The European Central Bank has today entered the next phase in introducing its own central bank digital currency – the “digital euro“.

A two-year investigation period will first involve discussions of policy objectives and use cases for the remainder of the year, followed by tradeoffs between privacy and other policy objectives such as anti-money laundering in early 2022.

After that, the impact on the financial system, particularly the drain on bank deposits and how to manage this, as well as the use of cash, are on the agenda. Another important element of the investigation will be the business models of private and public entities involved with the digital euro.

After the investigation phase, and a decision to continue in 2023, the actual development is scheduled to take around three years, which means the ECB has quietly added another year to the development phase, compared to its statements a few months ago.

This suggests that the general public may be introduced to a digital euro in 2026.

Today’s announcement is accompanied by an interesting overview of technical experimentation done on possible infrastructures, ranging from scaling the current TARGET Instant Payment Settlement or TIPS system to distributed ledger technology (DLT) and offline payments. The technical work shows that the ECB has initially cast the net wide. The document notes that “the sooner the scope of possible use cases can be narrowed down, the easier it will be to set up focused and specific technical investigations in the future.” This is a delicate observation, given that one of the most common remarks about CBDC outside central banks has been, “What problem is CBDC actually solving?”.

Indeed, while there is no shortage of (justified) motivations from a central bank and policymaker perspective to investigate CBDC, whether Eurozone citizens will actually be helped by, e.g. a faster, cheaper or more seamless payment experience than what is available today, remains to be seen.

It is, therefore, no coincidence that objectives and use cases are first on the agenda, as they should be.

One of the main motivations for the ECB to accelerate its work on CBDC has been the threat of privately issued stablecoins crowding out central bank money.

To be concrete, Facebook’s announcement of Libra back in 2019 is what jolted the Eurosystem into action. The ECB emphasises that “European intermediaries would be in a position to … stay competitive even as global tech giants expand into payments and financial services.” Indeed, if designed well and accompanied in a way for Europeans to identify themselves seamlessly and securely (to be helped along by the European Commission’s recent Digital Identity wallet proposal), a digital euro could foster diversity in Europe’s digital markets, but this is not the only possible scenario.

A digital euro, combined with a Europe-wide digital ID wallet, could also, in fact, strengthen large platforms, allowing them to integrate ID and digital euro building blocks into their platform. Their resulting ability to offer users complete on-platform, in-app experiences could weaken competitors outside the dominant platforms.

In designing the digital euro, there are a lot of moving parts, and it will be a challenge to get this right.

With the digital euro, there are still a lot of questions that need to be answered, and little can be taken as given at this stage. This also applies to the purported benefits, including financial inclusion, privacy, safety, and competition between digital services providers.

We think the time ahead will bring more clarity on what is feasible.

This article first appeared on ING THINK