The way we manage our daily money is changing rapidly, both visibly and behind the scenes. Effects will go beyond the disappearance of plastic cards

Payments: striving for integration, achieving more fragmentation?

Payments are seen as the plumbing of the economy. If that seems dull, rest assured, it isn’t anymore. It combines cutting edge tech developments, geopolitical arm-wrestling, stiff competition and central bank strategic manoeuvring.

Take Facebook’s Libra, a new cryptocurrency which threatens to disrupt the global financial system. After a strong backlash from global politicians and central bankers, it is unclear whether Libra will launch as planned in 2020. But with tech giants pushing deeper into finance, and bigtech already taking over payments in China, the industry looks set to be transformed in ways that have yet to be fully recognised.

The geopolitical importance of payment infrastructure is clear. The central role of the dollar in international finance means the US can wield power over foreign financials – power the US has been increasingly willing to use. It prompted, for example, the European Commission and European Central Bank to advocate more strongly for the development of a European retail payment infrastructure (as opposed to the current system reliant on the US firms Visa, Mastercard and Paypal, with expanding US and Chinese bigtech payment front-ends), and to develop plans to promote the international role of the euro.

Given their potentially far-reaching consequences, digital currencies are rapidly turning into Boardroom material as well.

Libra, and the strategic importance of money and payments, has prompted some major central banks to perform a U-turn on central bank digital currencies (CBDC). Before 2019, CBDC was mostly a debate for monetary seminars, now, it’s a topic of key strategic relevance for central bankers. As the Bank for International Settlements puts it, 20% of the world’s population may be using retail CBDC in the next three years. Both private and central bank digital currencies could have disruptive implications for banks. Bank disintermediation changes the channels of monetary transmission and raises fundamental questions about the operational framework of monetary policy. Mitigation of consequences for the availability of bank lending might involve central banks extending funding to banks, or taking on a greater role in credit provision themselves. Neither of these options look very attractive from a central bank perspective. At an even more fundamental level, the emergence of new digital currencies may fuel the debate about bank money creation, involving a total rethink of the financial plumbing of our economies. Given these potentially far-reaching consequences, digital currencies are rapidly turning into Boardroom material as well.

Last year, an EU directive known as PSD2 entered into force. In the UK, this is known as “Open Banking”. The “APIfication” of payments opens up the system to all kinds of new non-bank players. Paradoxically, individual service providers aim to provide a seamless, integrated service to their clients. The ideal often mentioned is an all-inclusive “super app”, like WeChat or TaoBao, which caters for all the clients’ needs, and makes any other app superfluous. At the same time, research into new currencies, both private and public, and the suspicion about the role of global players could actually result in a more fragmented back-end.

What to expect in the years ahead?

For crypto-assets, the future is with those initiatives that embrace and work with regulation

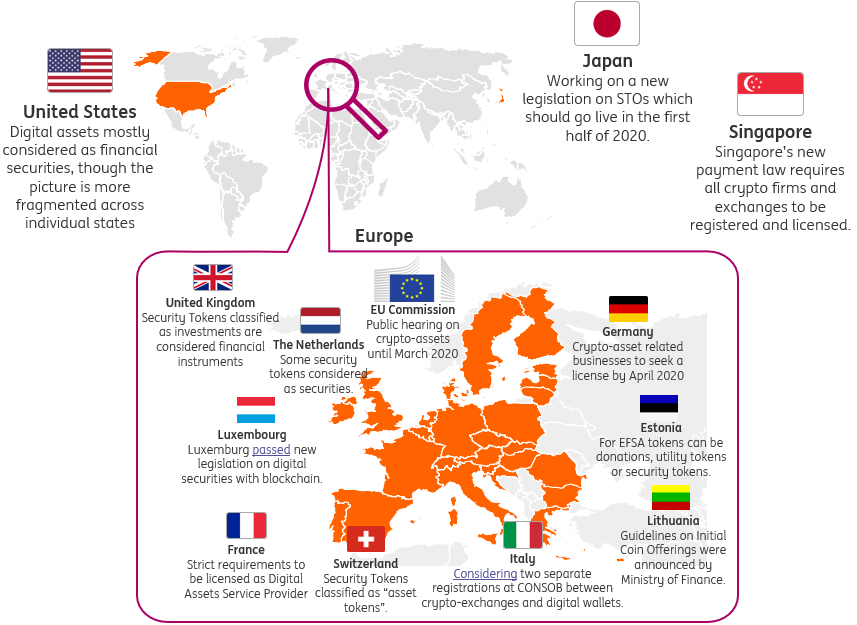

We remain of the opinion that a niche role is the best that ‘legacy’ crypto-assets can hope for as long as they continue to try and work around regulation. The future is with initiatives that embrace and work with regulation. Moreover, the debate is moving towards digital assets, with the industry making further progress on asset custody solutions, and regulators playing catch-up quickly this year, especially (perhaps surprisingly) in Europe. France strengthened its regulatory framework by issuing the Pacte Act last year. This new legislation brings more clarity on primary digital assets issuance, and allows Digital Asset Service Providers (DASPs) to operate in secondary markets. It also imposes some prudential and anti-money laundering measures. Germany created a new licensing regime for digital asset custody. Europe is now one of the most active regions in developing asset tokens and their legal framework, with Switzerland, Germany and France leading the way. However, to avoid fragmentation across jurisdictions, coordination and standardisation are needed. This would also bolster cross-border activity, which in turn would strengthen Europe’s credentials as a digital market.

2020: digital asset regulation in full swing

Meanwhile, the CBDC debate and research are accelerating. We expect more progress on the wholesale front first, with a key focus on improving efficiency, speed and costs while reducing counterparty risks. At the same time, central banks have stepped up their research on retail CBDC, but given the potentially more disruptive nature, they are likely to be careful and take it slow. In the developed world, the RiksBank is definitely the most “progressive” central bank on CBDC research with its e-krona project, in the face of steeply declining cash use. Before issuing e-krona, however, the central bank needs to make sure that it has a clear mandate from the Swedish parliament, and so far, nothing has been decided. The People’s Bank of China is also doing some serious work, having filed over 80 patents, and we should be ready for some potentially ground-breaking announcements in 2020. The PBoC is looking to preserve and build on the well-developed domestic digital payments infrastructure, while issuing and controlling CBDC centrally.

Wholesale central bank currency may soon hit the wholesale market

2020: the digital currency race gets global

As for Libra, Facebook has suggested it could drop its currency basket approach and instead build separate €-libra, $-libra currency tokens. While many of Libra’s corporate backers have walked away from the project following objections from regulators and central bankers, we still expect them to return with Libra 2.0. If Libra (or another bigtech, for that matter) is able to establish a globe-spanning payments infrastructure, coupled with a unified digital ID scheme, it would be a major threat for banks and existing payment infrastructures in general.

A globe-spanning payments infrastructure with a unified digital ID scheme would be a major threat to existing infrastructures

Could this mark the end of good old notes and coins? Lower acceptance of cash transactions might further marginalise the unbanked and may not be socially desirable. In the United States, for example, the city council of New York joined San Francisco and Philadelphia in forcing retail stores to continue to accept physical cash. Within Europe, usage of and attitudes towards the continued availability of physical cash vary markedly between countries.

Physical cash still dominant?

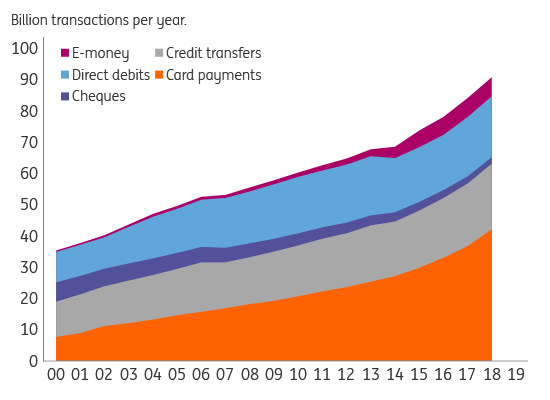

There were 90 billion non-cash payments in 2018 in the eurozone, or on average 2,854 every second. The latest eurozone survey on cash usage showed that in 2016, there were an estimated 129 billion cash transactions. Since 2016, non-cash payments increased by a cumulative 16%. It seems safe to assume that the number of cash transactions declined over that period, but that cash is still the dominant means of payment in the eurozone. We are probably not far off the turning point, though.

Euro area non cash payment services

The impact goes beyond the disappearance of plastic from your wallet

Policymakers have their work cut out for them in the years ahead: adjust customer due diligence and competition, privacy and digital ID frameworks, managing (geo)politics, and not least minimising the monetary and financial consequences. Central banks understandably want to take the time to think through all these aspects of digital currencies. The question is whether private sector initiatives allow them the time to do so.

This article first appeared on ING THINK